Monday, October 10, 2016

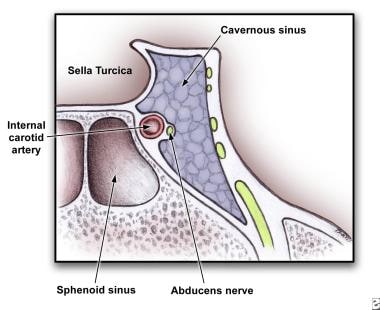

carvenous sinus thrombosis

Patients generally have sinusitis or a midface infection (most commonly a furuncle) for 5-10 days. In as many as 25% of cases in which a furuncle is the precipitant, it will have been manipulated in some fashion (eg, squeezing, surgical incision).

The clinical presentation is usually due to the venous obstruction as well as impairment of the cranial nerves that are near the cavernous sinus.

Headache is the most common presentation symptom and usually precedes fevers, periorbital edema, and cranial nerve signs. The headache is usually sharp, increases progressively, and is usually localized to the regions innervated by the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the fifth cranial nerve.

In some patients, periorbital findings do not develop early on, and the clinical picture is subtle.

Some cases of CST may present with focal cranial nerve abnormalities possibly presenting similar to an ischemic stroke.[2]

As the infection tracts posteriorly, patients complain of orbital pain and fullness accompanied by periorbital edema and visual disturbances.

Without effective therapy, signs appear in the contralateral eye by spreading through the communicating veins to the contralateral cavernous sinus. Eye swelling begins as a unilateral process and spreads to the other eye within 24-48 hours via the intercavernous sinuses. This is pathognomonic for CST.

The patient rapidly develops mental status changes including confusion, drowsiness, and coma from CNS involvement and/or sepsis. Death follows shortly thereafter.

Tx:

source: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/791704-clinical#b1

metronidazole

http://patient.info/medicine/metronidazole-for-infection-flagyl

Metronidazole is used to treat a wide variety of infections caused by anaerobic bacteria and micro-organisms called protozoa. These types of organisms often cause infections in areas of the body such as the gums, pelvic cavity and abdomen because they do not need oxygen to grow and multiply. It is commonly prescribed to treat an infection called bacterial vaginosis. It is also prescribed before gynaecological surgery and surgery on the intestines, to prevent infection from developing. Metronidazole can safely be taken by people who are allergic to penicillin.

Thursday, October 6, 2016

Monday, October 3, 2016

Dysphagia

DYSPHAGIA MNEMONIC (DIFFICULTY SWALLOWING):

Having trouble remembering all the important questions to ask during your patient encounter? Then try this Dysphagia Mnemonic (difficulty swallowing) for USMLE Step 2 CS.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION for Dysphagia Mnemonic

NOTE: Make sure to wash your hands or wear gloves before you start physical examination. Make sure to ask for permission before you start each physical exam. Make sure to use proper draping(don’t forget to tie back patient’s gown). Make sure to explain each physical examination in layman’s term to your patient. Do NOT repeat painful maneuvers.

- HEENT: Check throat for erythema and exudate

- Neck exam: Check for lymphadenopathy, thyromegaly

- Cardiovascular exam: Auscultation

- Pulmonary exam: Auscultation

- Abdominal exam: Inspection, auscultation, palpation, percussion.

- Skin: check for signs of scleroderma/CREST.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS for Dysphagia Mnemonic

- Esophageal cancer (Dysphagia starts with Solids and progresses to liquids. Hx of chronic alcoholism, smoking & weight loss )

- Achalasia (Dysphasia for BOTH solid and liquids)

- Esophagitis (Pain on swallowing. Immunocompromised “e.g. HIV, Corticosteroids”)

- Systemic Sclerosis (Look for CREST syndrome)

- GERD (Cough at nights, Hoarseness, sore throat)

- Plummer-Vinson syndrome (Iron deficiency anemia, sore throat, craving ice, dirt, clay…)

- Zenker diverticulum (Halitosis, regurgitation)

- Pill-induced esophagitis (e.g. Bisphosphonates)

- Mitral Stenosis (look for an immigrant or a pregnant female)

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP for Dysphagia Mnemonic

- CBC

- Serum iron, ferritin, TIBC

- Throat culture

- HIV antibody and viral load, CD4 count

- Chest X-ray

- Barium swallow

- Endoscopy

- Esophageal manometry

- Chest CT

http://www.medical-institution.com/dysphagia-mnemonic-difficulty-swallowing-usmle-step-2-cs-mnemonics/

GI mnemonics

- Bowel Segments

- "Dow Jones Industrial Averages Closing Stock Report" is a good one, even though it misses the Cecum...

Dow

Jones

Industrial

Averages

Closing

Stock

ReportDuodenum

Jejunum

Ileum

Appendix

Colon

Sigmoid

Rectum - Liver Lobes

- The four lobes of the liver: caudate, quadrate, left and right, bring to mind the newspaper headline of the wheelchair bound fellow who left a party right after his ugly girlfriend departed: "QUAD LEFT RIGHT after COW-DATE"

- Pertoneum Facts

- The idea is to relate key letters of related parts...

- stOMach and OMentum (which lays over the stomach)

The bacterium e. coLI is found in the Large Intestine

The OMentum covers the stOMach

The Lesser OMentum holds the Liver and stOMach

The Mesentery holds the sMall intestine

The mesoCOLON attaches the large intestine (COLON) to the posterior abdominal wall.

The periTONEa, which prevents the intestines from kinking, TONES the GI tract. - Sphincters of the Ailmentary Canal

- APE OIL initials the five of them...

A

P

E

O

I

LAnal

Pyloric

(Lower) Esophageal

Oddi

Ileocecum

iLeocecum - Stomach Parts

- "The CAR is FUN 'til the BODY PILES" relates the four parts of the stomach: Cardiac, Fundus, Body, Pylorus. The pylorus is where the food piles waiting for the sphincter to open.

Ulcerative colitis: definition of a severe attack A STATE:

Anemia less than 10g/dl

Stool frequency greater than 6 stools/day with blood

Temperature greater than 37.5

Albumin less than 30g/L

Tachycardia greater than 90bpm

ESR greater than 30mm/hr

Anemia less than 10g/dl

Stool frequency greater than 6 stools/day with blood

Temperature greater than 37.5

Albumin less than 30g/L

Tachycardia greater than 90bpm

ESR greater than 30mm/hr

Vomiting: extra GI differential VOMITING:

Vestibular disturbance/ Vagal (reflex pain)

Opiates

Migrane/ Metabolic (DKA, gastroparesis, hypercalcemia)

Infections

Toxicity (cytotoxic, digitalis toxicity)

Increased ICP, Ingested alcohol

Neurogenic, psychogenic

Gestation

Pancreatitis (acute): causes GET SMASHED:

Gallstones

Ethanol

Trauma

Steroids

Mumps

Autoimmune (PAN)

Scorpion stings

Hyperlipidemia/ Hypercalcemia

ERCP

Drugs (including azathioprine and diuretics)

· Note: 'Get Smashed' is slang in some countries for drinking, and ethanol is an important pancreatitis cause.

IBD: surgery indications "I CHOP":

Infection

Carcinoma

Haemorrhage

Obstruction

Perforation

· "Chop" convenient since surgery chops them open.

Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) cause is DNA mismatch repair DNA mismatch causes a bubble in the strand where the two nucleotides don't match.

This looks like the ensuing polyps that arise in the colon.

IBD: extraintestinal manifestations A PIE SAC:

Aphthous ulcers

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Iritis

Erythema nodosum

Sclerosing cholangitis

Arthritis

Clubbing of fingertips

Digestive disorders: pH level With vomiting both the pH and food come up.

With diarrhea both the pH and food go down.

H. Pylori treatment regimen (rough guidelines) "Please Make Tummy Better":

Proton pump inhibitor

Metronidazole

Tetracycline

Bismuth

· Alternatively: TOMB:

Tetracycline

Omeprazole

Metronidazole

Bismuth

Bilirubin: common causes for increased levels "HOT Liver":

Hemolysis

Obstruction

Tumor

Liver disease

Hemolysis

Obstruction

Tumor

Liver disease

Ulcerative colitis: complications "PAST Colitis":

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Ankylosing spondylitis

Sclerosing pericholangitis

Toxic megacolon

Colon carcinoma

Cholangitis features CHOLANGITITS:

Charcot's triad/ Conjugated bilirubin increase

Hepatic abscesses/ Hepatic (intra/extra) bile ducts/ HLA B8, DR3

Obstruction

Leukocytosis

Alkaline phosphatase increase

Neoplasms

Gallstones

Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis)

Transaminase increase

Infection

Sclerosing

Charcot's triad/ Conjugated bilirubin increase

Hepatic abscesses/ Hepatic (intra/extra) bile ducts/ HLA B8, DR3

Obstruction

Leukocytosis

Alkaline phosphatase increase

Neoplasms

Gallstones

Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis)

Transaminase increase

Infection

Sclerosing

Charcot's triad (gallstones) "Charge a FEE":

Charcot's triad is:

Fever

Epigastric & RUQ pain

Emesis & nausea

Haemachromatosis complications "HaemoChromatosis Can Cause Deposits Anywhere":

Hypogonadism

Cancer (hepatocellular)

Cirrhosis

Cardiomyopathy

Diabetes mellitus

Arthropathy

Pancreatitis: criteria PANCREAS:

PaO2 below 8

Age >55

Neutrophils: WCC >15

Calcium below 2

Renal: Urea >16

Enzymes: LDH >600; AST >200

Albumin below 32

Sugar: Glucose >10 (unless diabetic patient)

Pancreatitis: Ranson criteria for pancreatitis: at admission "GA LAW" (GA is abbreviation for the U.S. state of Georgia):

Glucose >200

AST >250

LDH >350

Age >55 y.o.

WBC >16000

Pancreatitis: Ranson criteria for pancreatitis: initial 48 hours "C & HOBBS" (Calvin and Hobbes):

Calcium < 8

Hct drop > 10%

Oxygen < 60 mm

BUN > 5

Base deficit > 4

Sequestration of fluid > 6L

Pancreatitis: Ranson criteria for pancreatitis at admission LEGAL:

Leukocytes > 16.000

Enzyme AST > 250

Glucose > 200

Age > 55

LDH > 350

GIT symptoms BAD ANAL S#!T:

Bleeding

Abdominal pain

Dysphagia

Abdominal bloating

Nausea & vomiting

Anorexia/ Appetite changes

Lethargy

S#!ts (diarrhea)

Heartburn

Increased bilirubin (jaundice)

Temperature (fever)

Crohn's disease: morphology, symptoms CHRISTMAS:

Cobblestones

High temperature

Reduced lumen

Intestinal fistulae

Skip lesions

Transmural (all layers, may ulcerate)

Malabsorption

Abdominal pain

Submucosal fibrosis

Dysphagia: differential DISPHAGIA:

Disease of mouth and tonsils/ Diffuse oesophageal spasm/ Diabetes mellitus

Intrinsic lesion

Scleroderma

Pharyngeal disorders/ Palsy-bulbar-MND

Achalasia

Heart: eft atrium enlargement

Goitre/ myesthenia Gravis/ mediastinal Glands

Infections

American trypanosomiasis (chagas disease)

21

Dry mouth: differential "DRI":

·2 of each:

Drugs/ Dehydration

Renal failure/ Radiotherapy

Immunological (Sjogren's)/ Intense emotions

Liver failure: decompensating chronic liver failure differential HEPATICUS:

Haemorrhage

Electrolyte disturbance

Protein load/ Paracetamol

Alcohol binge

Trauma

Infection

Constipation

Uraemia

Sedatives/ Shunt/ Surgery

·2 of each:

Drugs/ Dehydration

Renal failure/ Radiotherapy

Immunological (Sjogren's)/ Intense emotions

Liver failure: decompensating chronic liver failure differential HEPATICUS:

Haemorrhage

Electrolyte disturbance

Protein load/ Paracetamol

Alcohol binge

Trauma

Infection

Constipation

Uraemia

Sedatives/ Shunt/ Surgery

Cirrhosis: causes of hepatic cirrhosis HEPATIC:

Hemochromatosis (primary)

Enzyme deficiency (alpha-1-anti-trypsin)

Post hepatic (infection + drug induced)

Alcoholic

Tyrosinosis

Indian childhood (galactosemia)

Cardiac/ Cholestatic (biliary)/ Cancer/ Copper (Wilson's)

Hemochromatosis (primary)

Enzyme deficiency (alpha-1-anti-trypsin)

Post hepatic (infection + drug induced)

Alcoholic

Tyrosinosis

Indian childhood (galactosemia)

Cardiac/ Cholestatic (biliary)/ Cancer/ Copper (Wilson's)

Hepatic encephalopathy: precipitating factors HEPATICS:

Hemorrhage in GIT/ Hyperkalemia

Excess protein in diet

Paracentesis

Acidosis/ Anemia

Trauma

Infection

Colon surgery

Sedatives

Diabetic ketoacidosis: precipitating factors · 5 I's:

Infection

Ischaemia (cardiac, mesenteric)

Infarction

Ignorance (poor control)

Intoxication (alcohol)

Whipple's disease: clinical manifestations SHELDA:

Serositis

Hyperpigmentation of skin

Eating less (weight loss)

Lymphadenopathy

Diarrhea

Arthritis

Celiac sprue gluten sensitive enteropathy: gluten-containing grains BROW:

Barley

Rye

Oats

Wheat

· Flattened intestinal villi of celiac sprue are smooth, like an eyebrow.

Liver failure (chronic): signs found on the arms CLAPS:

Clubbing

Leukonychia

Asterixis

Palmar erythema

Scratch marks

Clubbing

Leukonychia

Asterixis

Palmar erythema

Scratch marks

Splenomegaly: causes CHIMP:

Cysts

Haematological ( eg CML, myelofibrosis)

Infective (eg viral (IM), bacterial)

Metabolic/ Misc (eg amyloid, Gauchers)

Portal hypertension

Source: http://www.valuemd.com/gastro.php

Pancreatitis

Source: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:7OvEopugpDkJ:unmhospitalist.pbworks.com/f/31.1-24%2520to%25201-30%2520Resident%2520Pancreatitis%2520Module.doc+&cd=20&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

Resident Version

Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis Module

Created by Dr. Teodora Konstantinova

Objectives:

1. List two differences in the diagnosis of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

2. Name 4 risk factors for developing pancreatitis

3. List two differences between treatment approaches to acute and chronic pancreatitis

4. Use Ranson criteria to predict severity of acute pancreatitis.

References:

1. Whitcomb D. C., Acute pancreatitis, N Engl J Med 2006, 354:2142-2150

2. Steinberg W, Tenner S, Medical Progress: Acute pancreatitis, NEnglJMed 1994, 330:1198-1210

3. Michael L. Steer, MD, Irving Waxman, MD and Steve Freedman, MD, Medical progress: Chronic Pancreatitis, N Engl J Med 1995, 332:1482-1490

4. Ranson JH, Diagnostic Standards for Acute Pancreatitis World J Surg 1997, 21:136-42

CASE:

HPI: A 60 yo female presents to the ER with severe mid-epigastric pain with radiation to the back, nausea and vomiting that started after lunch the previous day. Vomiting did not relieve the pain. The patient also reports coughing with yellow sputum for about a day. She doesn’t report fever, but states she has “chills” post emesis.

PMH:

HTN, depression, GERD, and menopausal symptoms requiring hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The patient also recently completed a course of nitrofurantoin for cystitis.

PSH: cholecystectomy 6 months ago.

Social hx: Patient has no history of alcohol abuse.

Medications:Lisinopril, Paxil, cimetidine, estrogen and completed course of nitrofurantoin 2 days ago.

Physical exam: VS: 100/60, P- 110, R-16, T-37.0 C, P02 - 87 % on RA.

The exam is significant for left lower lung field rales and egophany. The patient also had moderate mid-epigastric and RUQ tenderness without rebound or guarding. The rest of the exam is unremarkable.

Labs:

wbc: 16.5, H/H: 12/45

electrolytes are WNL

SGOT/SGPT: 500/400 U/l, alkaline phosphatase 400 U/l , total Bi 2.0 mg/dL

LDH: 860 IU per liter, serum lipase-5000, serum amylase- 2000, TG- 300

UA which is neg for LCE, nitrites, bacteria, WBCs or RBCs.

1. At this point in your evaluation, what should you initially be concerned about?

2. What could be the etiologies of this patient’s pancreatitis?

3. What radiologic studies should you consider obtaining?

4. Are you able to calculate your patient’s Ranson’s score?

Discussion Outline:

I. Differences between acute and chronic pancreatitis:

Acute and chronic pancreatitis are distinguished from each other on the basis of structural and functional criteria.

1. Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory condition of the pancreas. Acute disease is characterized by a normal pancreas that becomes inflamed prior to the attack and once the attack resolves the pancreas returns to normal.

2. Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive disorder of the pancreas that causes destruction of the pancreas. It involves long-term inflammation and scarring of the pancreas that is irreversible.

II. Pathogenesis:

Acute pancreatitis:

1. It relates to inappropriate activation of trypsinogen to trypsin (the key enzyme in the activation of pancreatic zymogens and a lack of prompt elimination of active trypsin inside the pancreas.

2. Activation of digestive enzymes causes pancreatic injury and results in an inflammatory response that is out of proportion to the response of other organs to a similar insult.

3. The acute inflammatory response itself causes substantial tissue damage and may progress beyond the pancreas to a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, multiorgan failure and death.

Chronic pancreatitis:

1. The hypersecretion of protein from acinar cells in the absence of increased fluid or bicarbonate secretion from duct cells is characteristic of chronic pancreatitis.

2. Plugs formed by the precipitation of protein within the interlobular and intralobular ducts are an early finding.

3. The plugs contain multiple proteins (digestive enzymes, glycoproteins, and acidic mucopolysaccharides).

4. The precipitation of calcium carbonate in the plugs results in the formation of intraductal stones (this is more common in patients with alcohol-induced or tropical pancreatitis).

5. Patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis frequently have an elevated pressure in the pancreatic duct.

III. Causes of pancreatitis:

1. Gallstones (45 % of cases)

2. Alcohol (35 % of cases)

3. Drugs: Azathioprine, Mercaptopurine, Valproic acid, Estrogen, Tetracyclines, Metronidazole, Nitrofurantion, Pentamidine, Lasix, Sulfonamides, Methyldopa, Cimetidine, Ranitidine, Salicylates, Erythromycin

4. Metabolic abnormalities: Hypercalcemia, Hypertriglyceridemia

5. Trauma: accidental or iatrogenic (ERCP, postoperative, endoscopic sphincterotomy)

6. Infections:

Parasitic (ascariasis, clonorchiasis)

Viral (mumps, rubella, Hepatitis A, B, non-A, non-B, coxsackievirus B, Echo virus, adenovirus, varicella, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV virus)

Bacterial: (mycoplasma, Campylobacter jejuni, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Legionella, Leptospirosis)

7. Miscellaneous causes: penetrating PUD, Crohn’s disease, Reye’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis)

8. Idiopathic (10% of cases)

IV. Diagnosis

Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis:

1. Characteristic abdominal pain (begins in the upper abdomen and spreads through the back)

2. Nausea and vomiting (usually the vomiting doesn’t relief the pain)

3. Elevated serum levels of pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase)

4. Both enzymes remain elevated with ongoing pancreatic inflammation, with amylase level typically returning to normal shortly before lipase levels in the resolution phase.

5. Imaging:

- Ultrasound of the abdomen remains the most sensitive method of evaluating the biliary tract in acute pancreatitis. It has a sensitivity of 67% in the urgent diagnosis, and a specificity of 100%.

- CT scan is the imaging method of choice in delineating the pancreas, as well as in determining the severity and complications.

- ERCP plays a part in diagnosis in patients in whom no definite cause is found. Abnormalities revealed by this study include small pancreatic tumors, pancreatic ductal strictures, gallstones, pancreas divisum, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

Diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis:

1. In developed countries, most patients with chronic pancreatitis have a history of prolonged and heavy alcohol use. They typically have recurrent attacks of upper abdominal pain, which may radiate to the mid-back, nausea and vomiting.

2. 10-20 % of patients have “painless” pancreatitis. They may present with DM, jaundice, malabsorption, steatorrhea with weight loss.

3. Malabsorption resulting from exocrine insufficiency may cause fecal fat excretion to be elevated. Undigested fat is qualitatively detected by Sudan staining of feces.

4. Routine blood studies (such as amylase, lipase) do not necessary show elevations.

5. Plain film of the abdomen: The finding of pancreatic calcification is virtually diagnostic of chronic pancreatitis, but often this is not found.

6. There are several other tests: US , CT scan of the pancreas, ERCP, EUS, MRCP, MRI

7. ERCP is the gold-standard imaging procedure for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and planning treatment.

V. Treatment:

Acute pancreatitis:

1. Supportive therapy, vigorous IVF hydration, possible use of NG (especially with ileus and severe vomiting), correction of electrolytes.

2. Immediate endoscopic removal of impacted stones in patients with severe disease appears to reduce mortality.

3. Use of antibiotics: A potential role for prophylactic use of antibiotics in severe acute pancreatitis was initially given support by a randomized trial demonstrating that imipenem reduces infection complications.

Recent randomized trial failed to demonstrate differences in outcome among patients treated with Cipro and Flagyl, as compared with placebo, leading some experts to recommend against routine use of prophylactic antibiotics.

4. Nutritional support: ensuring adequate nutrition is important in patients with severe or complicated pancreatitis. Recent meta-analysis of 6 randomized trials involving a total of 263 patients demonstrated improved outcomes with enteral nutrition, including decreased rate of infections and surgical interventions, reduce length of hospital stay, reduced costs.

5. Decision on the appropriateness of surgical management of sterile necrotic tissue should be made on a case-by-case basis, however, infected necrotic tissue and infected collections of fluid are best treated by surgical debridement.

Chronic pancreatitis:

1. Pain: abstinence from alcohol, administration of analgesic medications, and nerve blocks. Exocrine insufficiency may lead to increased cholecystokinin-mediated stimulation of the pancreas. This process theoretically could be interrupted by administration of digestive enzymes (trypsin, cholecystokinin receptor antagonists, or somatostatin).

2. When the pain persists in spite of aggressive noninvasive therapy, patient should undergo ERCP to define the caliber and morphologic characteristic of the pancreatic ducts.

3. Malabsorption: when > 90 % of exocrine pancreatic function is lost, clinically overt malabsorption occurs. Treatment consists of low-fat diet. Medium chain triglycerides may be useful because their absorption depends on minimal amounts of pancreatic enzymes and does not require bile salts.

For persistent symptoms pancreatic-enzyme replacement should be given orally just before meals. Neutralization of gastric acid with orally administration bicarbonate, inhibition of acid secretion, or enteric coating of enzyme preparation may prevent degradation of these enzymes as they traverse the stomach.

4. Pseudocysts: develop in 10 % of patients. Most resolve spontaneously but hemorrhage into a pseudocyst, rupture or infection can occur.

Treatment is indicated for those who persist for 6 weeks or are either enlarging or cause symptoms. Treatment is resection, external or internal drainage.

5. Pancreatic ascites or pleural fistulas. Diagnosis is made if paracentesis or thoracentesis yields fluid high in protein and amylase. Currently the treatment is surgery.

VI. Predicting severity of acute pancreatitis:

Many models exist although none are ideal and most of them take about 48 hrs to complete assessment. They also do not have high sensitivity or specificity, although relying on routine clinical assessment identifies only 30-40% of patient with severe acute pancreatitis. These models are usually based on:

1. Presence or absence of organ failure, and local complications.

2. Systems that assess inflammation or organ failure (Ranson criteria)

3. Findings on imaging studies

Ranson criteria to predict severity of acute pancreatitis

At 0 Hours

Age > 55 yo

Wbc> 16 k

Glucose> 200 mg/dL

LDH> 350

SGOT (AST) > 250 Mortality per positive criteria:

0-2 <5% mortality

3-4 20% mortality

At 48hours 5-6 40% mortality

Hct fall by > 10% 7-8 100 % mortalit

BUN increase > 5 mg/dl despite fluids

Ca < 8 mg/dL

PO2 < 60 mm/Hg

Base deficit > 4mEq/L

Fluid sequestration > 6L

11 total criterias in Ranson scoring. The presence of 1 to 3 criteria represents mild pancreatitis; as the number of criteria increase, the severity of pancreatitis increase and so does the mortality associated with it.

Review Questions:

1. A 27 yo patient is admitted with acute pancreatitis. Four days after admission patient develops high fever with worsening abdominal pain. The examination reveals a T of 102F and marked upper abdominal tenderness without rebound. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast shows a solid mass and gram stain of the aspirate is positive for gram-negative organism.

Based upon the above information you will now recommend:

A) IV broad spectrum antibiotics.

B) IV antibiotics plus insert a CT –guided percutaneous drainage tube.

C) IV antibiotics plus surgical debridement.

2.. A 60 yo man with known chronic pancreatitis caused by alcohol reports a 25 lbs weight loss in the past several months and frequent, greasy, and malodorous stools. A 72- hour fecal fat collection confirms steatorrhea. The patient no longer consumes alcohol and reports no abdominal pain.

Which of the following is the most appropriate first-line treatment for this patient?

A) Administration of enteric-coated pancreatic enzyme replacement tablets with meals and snacks and concurrent use of a calcium containing antacids.

B) Administration of non-enteric-coated pancreatic enzyme replacement tablets with meals and snacks with concurrent dosing with a histamine2 blockers.

C) Endoscopic placement of a pancreatic dust stent.

D) Institution of a low-fat diet (less than 20 g fat/day).

E) Subcutaneous administration of octreotide daily.

Post Module Evaluation

Please place completed evaluation in an interdepartmental mail envelope and address to Dr. Wendy Gerstein, Department of Medicine, VAMC (111).

1) Topic of module:__________________________

2) On a scale of 1-5, how effective was this module for learning this topic? _________

(1= not effective at all, 5 = extremely effective)

3) Were there any obvious errors, confusing data, or omissions? Please list/comment below:

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

4) Was the attending involved in the teaching of this module? Yes/no (please circle).

5) Please provide any further comments/feedback about this module, or the inpatient curriculum in general:

6) Please circle one:

Attending Resident (R2/R3) Intern Medical student

GI resources

Gallbladder dz (excellent basic texts on anatomy, lab, tx!): http://fitsweb.uchc.edu/student/selectives/Luzietti/Gallbladder_anatomy.htm

GI case studies resources

http://www.mednet.gr/static_page/54

http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/MedEd/MEDICINE/cpc/case27/case_f.htm

https://lutheranmeded.com/research/elearning/gastro/

http://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/topic/gastroenterology#

http://www.hcplive.com/journals/resident-and-staff/2005/2005-04/2005-04_07

http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/MedEd/MEDICINE/cpc/case27/case_f.htm

https://lutheranmeded.com/research/elearning/gastro/

http://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/topic/gastroenterology#

http://www.hcplive.com/journals/resident-and-staff/2005/2005-04/2005-04_07

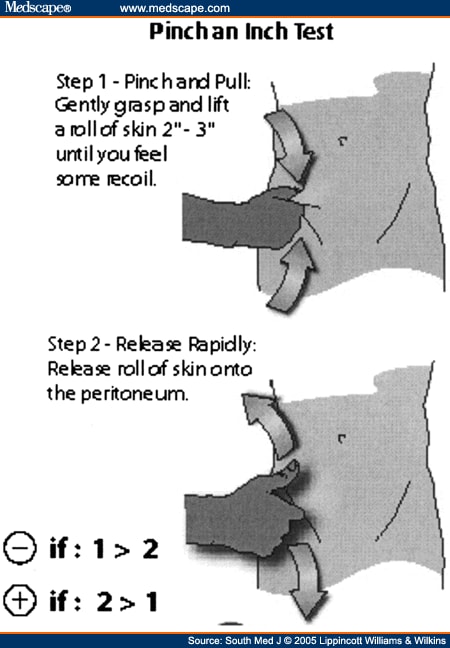

pinch an inch

Abstract and Introduction

Rebound tenderness is a widely used examination technique for patients with suspected appendicitis, but it can be quite uncomfortable. An alternative test for peritonitis is termed the pinch-an-inch test. This report describes two patients who presented with mild abdominal pain who subsequently were found to have appendicitis. In both patients, classic peritoneal signs were absent, but the pinch-an-inch test was positive. The experienced physician's bedside clinical examination remains the most critical component for rapidly identifying peritonitis. Although rebound tenderness is a widely used examination, it is uncomfortable and may be inaccurate. To perform the pinch-an-inch test, a fold of abdominal skin over McBurney's point is grasped and elevated away from the peritoneum. The skin is allowed to recoil back briskly against the peritoneum. If the patient has increased pain when the skin fold strikes the peritoneum, the test is positive and peritonitis probably is present.

Rebound tenderness, a widely used physical examination test for patients with suspected appendicitis, can be quite uncomfortable for the patient.[1,2] Accordingly, some standard references no longer advise its use on patients with abdominal pain.[3,4] We recently developed an alternative test for peritonitis that in our experience produces less discomfort for patients. We colloquially termed this peritoneal sign the pinch-an-inch test. To the best of our knowledge, others have not described it.

Our pinch-an-inch test is essentially a form of rebound tenderness, only in reverse. To perform the test, a fold of abdominal skin over McBurney's point is grasped and elevated away from the peritoneum (see Fig. 1). The skin is then allowed to recoil back briskly against the peritoneum. If the patient has increased pain when the skin fold strikes the peritoneum, the test is positive and peritonitis is presumably present. As an added feature, if the pain seems excessive just during the initial pinch phase, the patient may have a very low pain threshold, a factor that can be taken into account when deciding if the patient has a surgical abdomen. We anecdotally have found the test to be remarkably helpful for the evaluation of appendicitis as exemplified by the following cases.

Source: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/521231

Rebound tenderness

Blumberg sign (or Rebound tenderness positive sign) is elicited by palpating slowly and deeply over a viscus and then suddenly releasing the palpating hand. (2)

Rebound tenderness is tested for by pressing firmly and steadily on a patient's abdomen for a minute or two, and then releasing your hand suddenly. If he finds this agonizingly painful, the sign is positive. It is an uncomfortable and not a very reliable sign, and is most useful when pressure applied in one place causes rebound pain in another. For example, if pressure in his left lower abdomen causes pain in his right lower abdomen, it suggests appendicitis (Rovsing's sign). Many surgeons use light percussion, which is more accurate and much less cruel than rebound tenderness. (1)

1 - http://www.meb.uni-bonn.de/dtc/primsurg/docbook/html/x2980.html

2 - https://offlineclinic.com/blumbergs-sign-rebound-tenderness/

Rebound tenderness is tested for by pressing firmly and steadily on a patient's abdomen for a minute or two, and then releasing your hand suddenly. If he finds this agonizingly painful, the sign is positive. It is an uncomfortable and not a very reliable sign, and is most useful when pressure applied in one place causes rebound pain in another. For example, if pressure in his left lower abdomen causes pain in his right lower abdomen, it suggests appendicitis (Rovsing's sign). Many surgeons use light percussion, which is more accurate and much less cruel than rebound tenderness. (1)

1 - http://www.meb.uni-bonn.de/dtc/primsurg/docbook/html/x2980.html

2 - https://offlineclinic.com/blumbergs-sign-rebound-tenderness/

Sunday, October 2, 2016

study tips

https://www.quora.com/How-do-top-medical-students-study

In the spirit of providing concrete (and hopefully helpful!) advice: Here are some ideas to to be as efficient as possible to process, digest, and retain the deluge of information medical school offers: (or any vocational school for that matter):

ORGANIZATION:

Divide & Conquer. Categorize your study content into the following buckets:

After a full day of classes and workshops, many medical students find their study load to be dauntingly heavy, intimidating and disorganized. The content to learn is often significantly more voluminous and complicated than that of college and many students find themselves in uncharted territory trying to expand their mental bandwidth.

Take an hour after classes to systematically divide your study load into these categories. Once completed, take a breath and then conquer the first bucket:

Can I learn this right now in under 5-10 minutes?

Because these are low-hanging fruits, you will find that studying is manageable. Learning items in this category should be at a quicker pace and in a short 1-2 hours, you'll have accomplished a significant amount. Day by day, the baggy study load becomes organized and manageable which is KEY to efficiency. This approach also provides much needed motivation to tackle the more complicated and dense materials.

Teamwork.

No one makes it alone. Find your team. Your study group should be small enough where you must be a participating active member and not a passive silent participant. You have to trust your team: trust them enough to be comfortably wrong.

When organizing your study load, consider which elements can be potentially delegated to the study group (particularly if you lack interest or strength in an area and one of your team members has a particular passion for that subject). Why burn hours and mental anguish trying to understand renal pathophysiology when a friend can break it down for you in easy to understand principles and concepts? Likewise, things may be delegated to you at which point you'll find yourself teaching: an invaluable way to reinforce learning. An efficient and trusted team will shave off much waste and add significant value to your study time. (My team was a group of 4 trusted stalwarts: more than 10 years later we continue to remain close in friendship).

Can I put this off until later?

This is such an important element to organizing your material. Prioritizing the timeliness of your curriculum is a necessary tool to achieving sustainability in an increasingly additive workload. You minimize the waste of learning something that could have been put off at the cost of learning something you should have focused on due to an upcoming exam, rotation or workshop. Simply by taking the time to categorize when something should be learned will help you stay focused, in-the-moment, and never behind.

BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATIONS:

Most people believe your mind is your mind and there's little one can do to importantly augment how quickly you process information. But here are some thoughts than can make incrementally small differences to give you an edge:

These tips aren't meant for everyone. Learning styles are highly individualized - from toddlers to medical students. Visual, audio, oral, organized or procrastinator, repetition or photographic...the key is to gain insight into your personal styles and strengths (reference: Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences & Carl Jung's learning style dimensions). Having achieved entrance to medical school, chances are you are well aware of what works for you and what doesn't. Don't re-invent! Rather, build on what has already made you successful thus far.

I hope some of this is helpful. Now stop procrastinating and get back to studying!

In the spirit of providing concrete (and hopefully helpful!) advice: Here are some ideas to to be as efficient as possible to process, digest, and retain the deluge of information medical school offers: (or any vocational school for that matter):

ORGANIZATION:

Divide & Conquer. Categorize your study content into the following buckets:

- Can I learn this right now in under 5-10 minutes?

- Can I delegate this? (see teamwork below)

- Can I put this off until later?

After a full day of classes and workshops, many medical students find their study load to be dauntingly heavy, intimidating and disorganized. The content to learn is often significantly more voluminous and complicated than that of college and many students find themselves in uncharted territory trying to expand their mental bandwidth.

Take an hour after classes to systematically divide your study load into these categories. Once completed, take a breath and then conquer the first bucket:

Can I learn this right now in under 5-10 minutes?

Because these are low-hanging fruits, you will find that studying is manageable. Learning items in this category should be at a quicker pace and in a short 1-2 hours, you'll have accomplished a significant amount. Day by day, the baggy study load becomes organized and manageable which is KEY to efficiency. This approach also provides much needed motivation to tackle the more complicated and dense materials.

Teamwork.

No one makes it alone. Find your team. Your study group should be small enough where you must be a participating active member and not a passive silent participant. You have to trust your team: trust them enough to be comfortably wrong.

When organizing your study load, consider which elements can be potentially delegated to the study group (particularly if you lack interest or strength in an area and one of your team members has a particular passion for that subject). Why burn hours and mental anguish trying to understand renal pathophysiology when a friend can break it down for you in easy to understand principles and concepts? Likewise, things may be delegated to you at which point you'll find yourself teaching: an invaluable way to reinforce learning. An efficient and trusted team will shave off much waste and add significant value to your study time. (My team was a group of 4 trusted stalwarts: more than 10 years later we continue to remain close in friendship).

Can I put this off until later?

This is such an important element to organizing your material. Prioritizing the timeliness of your curriculum is a necessary tool to achieving sustainability in an increasingly additive workload. You minimize the waste of learning something that could have been put off at the cost of learning something you should have focused on due to an upcoming exam, rotation or workshop. Simply by taking the time to categorize when something should be learned will help you stay focused, in-the-moment, and never behind.

BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATIONS:

Most people believe your mind is your mind and there's little one can do to importantly augment how quickly you process information. But here are some thoughts than can make incrementally small differences to give you an edge:

- Sleep. All nighters to cram has diminishing returns. Lack of sleep and fatigue has been compared to a blood alcohol level of at least 0.1% in one Australian study. Your performance (exam, verbatim recall, etc) and your coordination (procedures, surgery) will be significantly better after a restful sleep.

- Caffeine. This is a drug. Overuse predictably lends oneself to dependence. The absence of this drug will predictably lead to a state of withdrawal and detract from performance and mental efficiency (headaches, moodiness, etc). PEARL: Use sparingly in key moments, caffeine will predictably AUGMENT mental efficiency. A group of us in medical school never drank coffee on a regular basis. We leveraged it by drinking it strategically right before an exam. Our bodies never got accustomed to it and much like an intermittent drug, we felt the augmented mental alacrity when taking it sparingly (n.b. we never experimented with nor recommend "stay awake drugs" such as Provigil).

- Stop multitasking. We live in an era where smartphones and tablets are constantly at our fingertips. Distractibility, attention-deficiency and hyper-activity are real phenomenons that children, young adults and professionals struggle with in this information-accessible culture. It is an addiction and the metaphorical quick-sand of efficient learning and productivity. Set predetermined times of studying and breaks to minimize these hazardous distractions.

These tips aren't meant for everyone. Learning styles are highly individualized - from toddlers to medical students. Visual, audio, oral, organized or procrastinator, repetition or photographic...the key is to gain insight into your personal styles and strengths (reference: Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences & Carl Jung's learning style dimensions). Having achieved entrance to medical school, chances are you are well aware of what works for you and what doesn't. Don't re-invent! Rather, build on what has already made you successful thus far.

I hope some of this is helpful. Now stop procrastinating and get back to studying!

study tips

https://meded.ucsd.edu/index.cfm/ugme/oess/study_skills_and_exam_strategies/how_to_study_actively/

HOW TO DRINK FROM A FIRE-HOSE WITHOUT DROWNING –

Four active processes will be used in the steps of any active study pattern and any study time that does not involve one or more of these steps is almost certainly passive and inefficient!

Many students find they lose sight of the forest as they focus on the leaves, much less the trees. If you notice you are getting lost during lecture, finding the "big picture" before lecture provides a road map through the forest that will increase active learning during lecture.

Organizing “necessary detail” into integrative summaries facilitates both memorization and application – and these summaries combine to form the “final draft” of your information that you will use to study for the final.

What are the most common problems medical students have with exams?

HOW TO DRINK FROM A FIRE-HOSE WITHOUT DROWNING –

Successful study strategies in medical school courses

April Apperson, UCSD SOM

Why should I change my study strategies?

If you're not happy with your performance, the most likely culprit is your study strategies. The material presented in medical school is not conceptually more difficult than many rigorous undergraduate courses, but the volume flow rate of information per hour and per day is much greater – it has frequently been described as “drinking from a fire-hose.”

- Everyone admitted to a medical school has study strategies successful for an undergraduate informational flow rate – unfortunately, those developed by most pre-meds are not efficient enough for the fire hose approach of medical school.

- The most fundamental principle of efficient studying – the best use of your limited time – requires active, not passive learning.

- Active learning requires making decisions about the material – “Is this important?”, “How is this part organized?”, “Where does this fit into the ‘big picture’?”, “What is the precise definition of this term?”,“Where have I seen this in an earlier lecture?

- Passive reading of pages of text or “going over” notes (even with a highlighter) and hoping to absorb the information is very inefficient –if you have enough time, it will work and probably did in undergraduate classes, but it usually isn’t adequate for the fire hose.

- Changing a habit isn’t easy, so don’t be surprised if you need to hear or review active strategies multiple times – it takes time to change.

What are the fundamentals of active studying?

Four active processes will be used in the steps of any active study pattern and any study time that does not involve one or more of these steps is almost certainly passive and inefficient!

- Identifying the important information – answering the eternal question of “what’s important here?”

- Organizing the information – start with the “big picture” to create a framework that facilitates memorization and access appropriate for differential diagnosis.

- Memorizing the information – this requires frequent review to keep it available for use!

- Applying the information to more complex situations – practice questions, quiz questions, clinical applications, etc.

Everyone will develop their own “high volume” study methods eventually, but the majority of medical students benefit from a starting strategy – and one generally successful starting point uses five basic steps:

- Finding the "big picture" by skimming the information before lecture – identifying and memorizing the four or five major topics will keep you on track during lecture.

- Creating a complete rough draft of the material by annotating the lecturer's slides – notes emphasizing the lecturer's context are supplemented as needed from other reading materials. Don't rewrite this!

- Creating summary charts, lists or diagrams that organize the needed material to emphasize patterns that facilitate memorization.

- Actively memorizing the charts, etc., as they are created, then incorporating quick and frequent review during later study to nail the information down – you'll still need the fundamentals after finals are over.

- Practicing application using practice or quiz questions during the study process – and not to test yourself just before the exam.

Why find the "big picture" before lecture?

Many students find they lose sight of the forest as they focus on the leaves, much less the trees. If you notice you are getting lost during lecture, finding the "big picture" before lecture provides a road map through the forest that will increase active learning during lecture.

Pre-lecture work should take no more than 10 minutes/hour lecture and has 2 goals:

- The road map. Scan the material to identify the number of major headings and the major subheadings each has, then take just a couple of minutes to memorize those (don't skip this part!). Read the introduction and summary, which emphasize those points.

- The vocabulary. Scan the material again to note any definitions or equations. Exact definitions are crucial and equations help relate many different factors correctly.

How do I generate my "rough draft" of all this information?

Take lecture notes that emphasize context – the big picture and what the instructor thinks is important.

- Much of the factual information is typically provided in a syllabus or a handout of a lecturer’s Power Point slides, so just annotate these – don’t forget you can use the backs of pages for your notes.

- Focus on adding context from the lecturer – this requires decision-making and so is active.

- On a power point graph, note the “point” a graph or chart is making, or clearly label the axes.

- Emphasize any comments of the lecturer on what is important information vs. what is just “color”.

- Always note circumstances that indicate when one reflex or response will outweigh another!

- Number the pages of lecture notes for each subject so that you can easily identify them. You will need those specific page numbers for cross-indexing your notes and references from your summaries.

- Use abbreviations and develop your own shorthand from them. Never write out the entire name of a macromolecule, gene, etc. after the first time. Use symbols for words whenever possible and be creative. Keep a list of them for the first quarter or two and be consistent. As they become habit, your speed will improve a lot.

Create the rough draft by labeling, annotating and cross-referencing your lecture notes as you read through them the first time – this is the messy but complete document you’ll use as source material for more concise summaries.

- Impose the “big picture” on your notes.

- Add major headings and subheadings within the notes and in the left margin in a different color ink – this reinforces the organization of the lecture. The lecture outline will frequently provide headings if they aren't apparent from the lecture slides.

- Label each topic in the left margin and circle specific definitions within the notes in a different color – these will be used both for reference and for keying memorization of the material.

- These processes force you to analyze the material and begin to actually learn it (not just track it); this will speed up integrative summary design, also.

- Supplement your notes with any additional information from other readings that will be needed to create effective summaries.

- Use your notes about the lecturer’s emphasis to help decide “what’s important”, and to look for missing information – if the lecturer discussed three abnormal conditions and provided causes for only two, maybe you missed the third.

- Use the index in the text to direct you to specific topics – don't get caught up passively reading large sections without actively pulling out the facts to incorporate into rough draft.

- Cross-index your notes between lectures – you won't remember which lecture contained each experiment the weekend before the final.

- Each time the lecturer mentions something you remember being discussed in an earlier lecture, stop, find the pages in your earlier notes and add the page numbers in both places.

- This makes it much easier to create summaries that contain the from multiple lectures – which are the most useful summaries!

Your rough draft is the single reference document you will refer to incase you need to add detail later to summaries or check on somethingyou originally didn't think was important.

How do I create organized summaries from my rough draft?

Organizing “necessary detail” into integrative summaries facilitates both memorization and application – and these summaries combine to form the “final draft” of your information that you will use to study for the final.

- What is "necessary" detail? See FAQ on "How do I know what will be on the exam?" or “How do I know how much detail to learn?”

- Different material lends itself to different types of summaries – simple lists, charts, flow diagrams, or pictures – use whatever combination you prefer.

- In each case, organize the material to emphasize connections and facilitate memorization.

- Where possible, create "big picture" organizations that integrate material from multiple lectures.

- If you're not sure whether to include a specific detail, leave it out and just put in an asterisk in the appropriate spot with the page number from your rough draft for quick reference.

- Don't recreate the wheel. If you find a good chart in some text orother source, photocopy it and add it to your summaries. Be sure to add any additional information to make it complete or more comprehensive —try a different color ink to make it stand out.

- Create and organize the headings before you spend any time filling in the actual information.

- The headings or location within a diagram should reinforce the “big picture” or anatomy or chronological sequence or steps in a physiological process or someaspect of the process.

- Finalize the organization of the headings for your list or chart, or the spatial organization for a flow chart or diagram before adding in any of the information (this uses up a lot of scrap paper).

- This requires analysis and integration of the material, which isactive, and aids memorization, since there is a "reason" for the orderor spatial organization.

- Use a hierarchical approach for headings or spatial organization – no more than five major headings on a list or chart or six major sections on a diagram — more is too hard to remember.

- If you need more headings or sections, decide how they are related and create subheadings.

- The same numerical limits apply to subheading – if necessary, go to the next level of subheadings.

- Make sure your headings (charts/lists) or spatial organization (flow charts, diagrams) provide information due to their sequence or location.

- The headings or location within a diagram should reinforce the “big picture” or anatomy or chronological sequence or steps in a physiological process or someaspect of the process.

- Multiple summaries or diagrams are better than one big one.

- Simple outlines in a syllabus provide a great source for topics that your summaries should cover.

- Limit the material covered in a single summary to an amount reasonable to memorize, then use multiple summaries to cover the material from different points of view.

- For complex material, the organization of the headings may not be enough to establish the "big picture"; in these cases, some summaries just focus on the big picture.

- Don't hesitate to include the same information on different summaries,especially if they are organizing the material from different points ofview or at different levels of detail.

How can I memorize actively and be sure I know the material?

- Don't put off memorizing material until just before the exam.

- Of course you will forget much of it after the first time — that's why you need to build repetitions into your study pattern. But if you memorized it actively (see above), you forget the "address" of the information much more than the actual information. So review will move it into long term memory. If you cram it the night before, you won't remember it a week later, much less the next quarter or the next year.

- So save the picky (but necessary) details for the night before, but memorize all the concepts and the first couple of levels of detail as you go and review them as you study later material.

- Memorize the headings first – their order should reinforce useful information like anatomy, time course, etc.

- First, memorize how many items (e.g., headings) there are

- Second, memorize the headings themselves – using biological logic, visualization, or mnemonics.

- Third, memorize the information associated with each heading, starting with just a key word or short phrase, and finally adding the full item.

- When you think you have memorized any piece of the chart, etc.:

- Cover the original, and write out the material on a blank piece of paper (don’t be pretty, but don’t cheat!), then throw what you have just written away!!!

- Look at the original – if you are confident you got it all – great! If there is any question, don’t compare with what you should have thrown away – just memorize it again.

- This method emphasizes what you don’t know; comparing the new with the old only confirms what you already knew, which misleads us into thinking we know more than we do.

- Quizzing each other is good motivation, but beware of subliminal cues used to help answer the questions without mastering the material. Explaining it out loud to yourself is a good start, but you can verbally "hand-wave" around areas you aren't clear on. Always check yourself as above.

- Frequent review is relatively painless with organized material – and extremely helpful.

- When an earlier topic or concept is mentioned, stop and review to yourself the relevant summary list – start with how many, then the headings, then the key words, then the concepts or facts.

- This review actually decreases the time needed to master later lectures, since later material builds on earlier; this also increases exam speed, since answering factual questions will be easier and faster.

How do I prepare for exam questions?

What are the most common problems medical students have with exams?

- Clarity of definitions or concepts vs. those derived from context.

- Students often generate their own general concepts or definitions from context – after all, that’s how we learn to speak – but this doesn’t provide enough clarity to analyze and correctly answer the questions.

- Medical terminology and equations are very precise – being “close enough” often isn’t sufficient.

- Familiarity with material vs. mastery of the material.

- “Familiarity” refers to recognizing the logic provided by someone else – as when leaving a good lecture, you can say, “yeah, that made sense.”

- Mastery of the material requires integration and memorization of sufficient detail that the information can be successfully applied to new situation.

- Good test questions discriminate between the two!

- Not having enough time to answer the more difficult applications questions involving multiple steps in feedback loops or multiple related equations.

- You need a method to approach complex question before you get to the exam.

- Use examples given in lecture, quiz questions, or other practice questions while you are studying to work out approaches for such questions ahead of time.

Where do I find time for all this?

- Successful high-volume studying relies on good investment strategies:

- Finding the “big picture” before lecture is easily put off, but it usually saves more time during creation of the rough draft.

- Creating summaries takes a lot of time, but it provides the "final draft" from which you study for the final – you won't have time to go back through the origninal notes!

- There is more time available in a day than you think – use it all.

- Divide your studying into a series of short tasks – don't wait until you have 2 or 3 hours to study. Use small bits of time while your clothes are drying or while the rice is cooking for dinner for a single task.

- Use all the "extra" time you can in the early weeks to be caught up in lectures and ahead on papers so there is some slop when it gets really intense.

- Be VERY careful about "robbing Peter to pay Paul" – it's inevitable, but try to keep it to a minimum. It’s tempting to completely quit keeping up with other classes to study for the upcoming exam, but this is a major trap – that class has a final, too. Usually, skipping class to do a paper or study for an exam ends up costing significantly more time in make-up time in the

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)